Talent management, in its purest sense, refers to a high-level HR strategy that sees to the optimal utilization of human capital to maximize an organization’s chances of success. But when it comes to managing a workforce, the human variable of the equation isn’t always easy to define and as such, predicting an outcome can be extremely arduous for managers who overlook important human behavior concepts, including motivation and aspiration.

Talent management, in its purest sense, refers to a high-level HR strategy that sees to the optimal utilization of human capital to maximize an organization’s chances of success. But when it comes to managing a workforce, the human variable of the equation isn’t always easy to define and as such, predicting an outcome can be extremely arduous for managers who overlook important human behavior concepts, including motivation and aspiration.

Success probably carries as many definitions as there are people walking the earth. To some, it’s a general disposition in life while for others, it is mostly centered around a specific aspect, such as career, finances or love. This diversity in the very definition of success is part of what makes developing and implementing a talent management approach so difficult for executives attempting to optimize workforce performance.

After all, your ‘incentives’ to performance must be broad enough to allow for a cost-effective, streamlined process, but they also need to be sufficiently customized to the varying needs of your employees.

Performance: A question of satisfying needs?

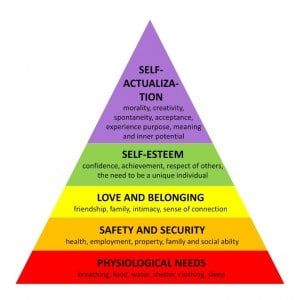

Most of us are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and how each level affects an individual’s behavior in life. But the continuation to this story, developed by David C. McClelland, is a little more obscure, despite the fact that his Need theory is often considered a major contributor to understanding human behavior in an organizational setting.

McClelland’s theory claims that humans possess three main needs, or motives – Achievement, Affiliation and Power – each of which dictate specific behaviors in the workplace.

| Motives | Characteristics |

| Achievement |

|

| Affiliation |

|

| Authority/Power |

|

Unlike Maslow’s theory under which it is understood that a person will not intentionally seek out to fulfill a need for as long as other more pressing, or basic, needs haven’t been fulfilled, the McClelland theory states that most people possess a combination of the above motives, to varying degrees based on culture and life experiences.

Based on this knowledge, the Need theory can help you optimize your talent management processes in a manner that is consistent with both your employees’ social ‘motives’ and your organizational need to maximize their performance.

Identifying your employees’ real motivation to performance

In a recent article, we discussed the importance of tapping into your workforce’s potential and interests to develop their competencies and create a culture of bar-raisers. According to this system, it is only “once employees understand the gap between their own skills and the competencies required by the position they aspire to attain” that training for optimal results begins to occur in the workplace, driven by employees’ need to succeed.

But success, as we previously mentioned, is a subjective matter, and it is ludicrous for an employer to assume that all employees aspire to be boss one day. Many are very content with fewer responsibilities in their careers, placing more emphasis on achieving success elsewhere in their life. What’s more, it is critical to have a diverse workforce to ensure performance at all levels of the organization.

McClelland’s theory assists us in accurately identifying your employees’ dominant need so that you may set appropriate goals (and expectations!), as well as provide the right feedback and incentives to get the best results out of every employee.

For instance, realizing that an employee possesses the potential to develop certain competencies required to access superior roles within your organization does not mean that your talent management system will succeed in unleashing it. Rather, McClelland’s study reveals that if the dominant motive of an employee under consideration for a managerial role is affiliation, presenting the benefits sought after by authority-driven individuals is unlikely to yield the intended results.

This can easily be compared to the effects of a customized value proposition on your business development strategies, relative to a generic proposal that doesn’t highlight the benefits sought after by the potential client. The potential of a new collaboration may be great, but failing to understand the motives of the person on the other side of the deal is unlikely to translate into the results you seek.

What’s good for the goose isn’t always good for the gander

By integrating and analyzing the most dominant need in your employees, you place yourself in a situation where you can adjust your own behavior and talent management approaches to drive superior results.

For instance, the theory proposes that to succeed in top management positions, a person should have a strong need for power and a low need for affiliation. And while authority-driven individuals are more likely to excel in these senior roles, it is achievement-motivated individuals who are better known for “making things happen and getting results”. But to encourage this behavior, employers need to provide constant feedback, with a fair share of praise. As such, when dealing with these employees, managers need to offer objective and regular performance reviews in order to set the pace for improvement and ultimately, superior results.

When combined with a customized competency-based approach to talent management, these insights into the characteristics of each person’s dominant motive to performance are critical to an organization’s success.

The case of ‘deliberate practice’, or the grooming of top performers

Once you have identified those employees who have 1) the competencies required by a given job role and 2) the motive to succeed in that role, it is important to assess the value of your professional development programs.

Scientific research shows that the quality and quantity of your coaching are as equally important, and that top performance is primarily the result of expert-level practice, NOT innate talent.

K. Anders Ericsson, a psychologist and scientific researcher at Florida State University, wrote a paper entitled The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance, in which he states:

“We argue that the differences between expert (top) performers and normal adults (employees) reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain.”

In other words, top performers – here referred to as ‘expert performers’ – are individuals who are developed to excel and deliver results. And this is where identifying the very motives that will drive an individual to train to become an expert performers becomes highly critical to the process.

To learn more about talent management, we invite you to browse other valuable articles and downloadable PDFs here, or join us at our next seminar.

To learn more about our products and services, and how competencies and competency models can help your organization, call 800-870-9490, email edward.cripe@workitect.com

To learn more about our products and services, and how competencies and competency models can help your organization, call 800-870-9490, email edward.cripe@workitect.com

or use the contact form at Workitect.

©️2024, Workitect, Inc.

Leave A Comment